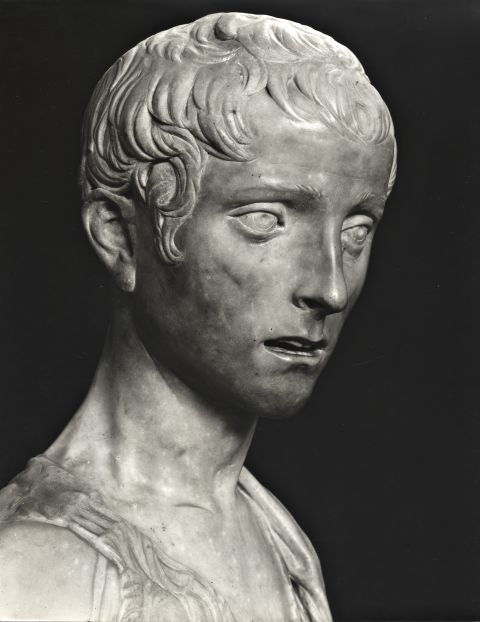

Martelli Saint John, ca. 1440-1457, Settignano and Donatello

Unconsciously, we tend to think more while we are waking than dreaming. So, we are ascending our-self to God by dreaming and reflecting on the days events or on previous psychological events. Most of Settignano's sculpture tend to be of small children or infants that make you feel like he had a wonderful childhood or beautiful wife and gorgeous babies. They do tend to represent either baby Jesus or Christ and Saint John the Baptist as young children or in early adulthood. You get the feeling Saint John tended his flock solo rather than in the company of a shepherdess. But the Saint John represented here does not feel old enough to have contemplated the dream of Saint Anthony. Rather he feels consumed with his own thoughts and contemplative philosophy.

Christ and Saint John the Baptist as Children, ca. 1455-1457,

Desiderio da Settignano, Musee du Louvre, Paris

Laughing Boy, ca. 1460-1464, Desiderio da Settignano,

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna